Tribute to Albert Camus

1913 – 1960

Part II

Anton Foek

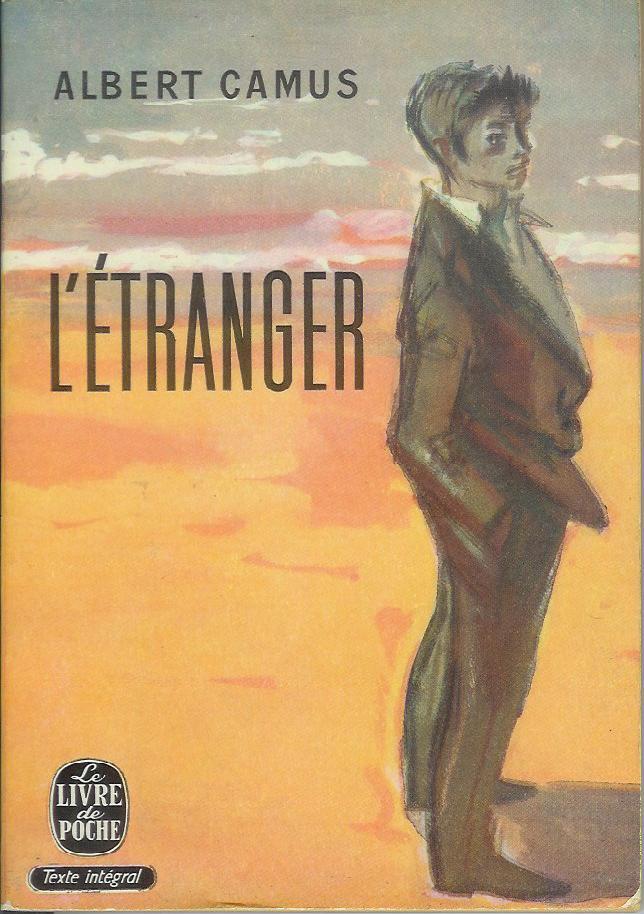

Amsterdam, June 2021– By 1943, he was back in France, to join the staff of the clandestine Resistance newspaper Combat, and publish those books: first the novel “The Stranger” and then a book of philosophical essays, “The Myth of Sisyphus.” The novel and the essays announced the same theme, though the novel did it on a downdraft and the essays on uplift: meaning is where you make it and life is absurd. In the novel, Camus meant absurd in the sense of pointless; in the essays in the sense of unjustified by certainty. Life is absurd because Why bother?

And life is also absurd because Who knows? The Stranger tells the story of an alienated Franco-Algerian, Meursault, who kills an Arab on the beach one day for no good reason. The no-good-reason is key: if it’s possible to act for no good reason, maybe there is never any reason to talk about “good” when you act. The world is absurd, Meursault thinks as does Camus, because, without divine order, or even much pointed human purpose, it’s just one damn thing after another, and you might as well be damned for one thing as the next: in a world bleached dry of significance, the most immoral act might seem as meaningful as the best one.

In Sisyphus, though, Camus offers a way to keep Meursault’s absurdity from becoming merely murderous: we are all Sisyphus, he says, condemned to roll our boulder uphill and then watch it roll back down for eternity, or at least until we die. Learning to roll the boulder while keeping at least a half smile on your face— “One must imagine Sisyphus happy” is his most emphatic aphorism — is the only way to act decently while accepting that acts are always essentially absurd. It was the editorials that Camus wrote for Combat that sustained his reputation. Editorial writers can seem the most insipid and helpless of the scribbling class: they sum up anonymously the ideas of their time, and truth and insipidity do a great deal of close dancing — the right thing to do is often hard but seldom surprising.

Good editorial writing has less to do with winning an argument, since the other side is mostly not listening, than with telling the guys on your side how they ought to sound when they’re arguing. It’s a form of conducting, really, where the writer tries to strike a downbeat, a tonic note, for the whole of his section. Not “Say this!” but “Sound this way!” is what the great editorialists teach.

What Camus wanted wasn’t new: just liberty, equality, and fraternity. But he found a new way to say it. Tone was what mattered. He discovered a way of speaking on the page that was unlike either the violent rhetorical clichés of Communism or the ponderous abstractions of the Catholic right. He struck a tone not of French or Parisian rancor but of melancholic loft. Camus sounds serious, but he also sounds sad — he added the authority of sadness to the activity of political writing.

He wrote with dignity, at a moment when restoring dignity to public language was necessary, and he slowed public language at a time when history was moving too fast. Responsibility, care, gradualness, humanity, even at a time of jubilation, these are the typical words of Camus, and they were not the usual words of French political rhetoric. The enemy was not this side or that one; it was the abstraction of rhetoric itself. He wrote, “We have witnessed lying, humiliation, killing, deportation, and torture, and in each instance it was impossible to persuade the people who were doing these things not to do them, because they were sure of themselves, and because there is no way of persuading an abstraction. Intoxication and joy were the last things that Camus thought freedom should bring. His watchwords were anxiety and responsibility. It was in the forties that Camus became intimate with Sartre.

Though each had known the other’s writing before meeting the writer, they became friends, in Saint-Germain, in 1943, a time when the Café de Flore was not an expensive spot but one of the few places with a radiator reliable enough to keep you warm in winter.

For the next decade, French intellectual life was dominated by their double act. Although Camus was married, and soon afterward had a mistress, and soon after that had twins, by his wife, readers are startled to realize that after the twins were born Camus’s life went on exactly as before — his deepest emotional attachment seems to have been to Sartre and his circle. Indeed, the image of the French philosophers in cafes debating existentialism dates from that moment and those men. Before that, Frenchmen in cafes debated love.