Inspiration and Love in Antibes

Françoise Gilot and Picasso

A.F.

Amsterdam/Antibes, August 18th 2021– Overlooking the Riviera coast, the Château Grimaldi in Antibes provides a dramatic setting for the world’s first museum dedicated to the works of Pablo Picasso

The imposing medieval fortress in Antibes known as the Château Grimaldi was used by Pablo Picasso as a studio in 1946, and in 1966 it was officially opened as a museum dedicated to the Spanish artist, with dozens of paintings and drawings being donated by Picasso himself.

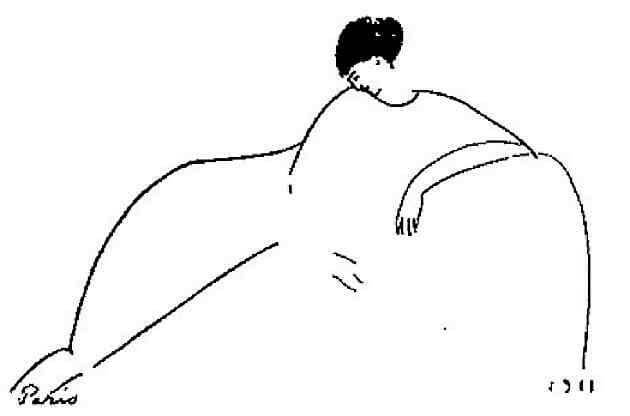

More works, including etchings and ceramics, were left to the museum by Picasso’s second wife, Jacqueline, and today the Musée Picasso holds 245 of his works, as well as paintings and sculptures by other modern artists including Nicolas de Staël, Joan Miró, and Amedeo Modigliani, who had invited the Anna Achmatova, the Russian poet to come over and inspire him to his create his own masterpieces.

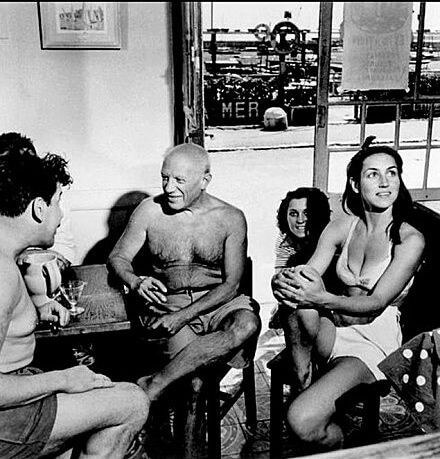

In the summer of 1946, Picasso and his lover Françoise Gilot left Paris and headed for the south of France to stay with an engraver friend, Louis Fort. In her book Life with Picasso, Gilot describes the tiny hamlet of Golfe-Juan, on the coast between Antibes and Cannes, as almost deserted when they first visited. These days the area heaves with tourists and the beach is lined with sun loungers and expensive restaurants.

It was on this beach that Picasso met another friend, the photographer Michel Sima, who told him about the space at Château Grimaldi, a Roman fort that was rebuilt in the 14th century and bought by the French crown.

Now owned by the city of Antibes, it had been renamed Musée Grimaldi and housed archaeological artefacts. The museum’s curator was struggling to fill its vast space and was more than happy to devote the former guards’ hall on the second floor to Pablo Picasso as his studio. The artist’s sojourn may have been brief – he stayed roughly from the middle of September to mid- November of that year – but his output was prodigious: 23 paintings and 44 drawings came out of his two months in Antibes.

When he moved in, Picasso told the curator that he would decorate the walls of the castle as a thank you.

But they were in a rough state of repair, and in the end Picasso was unable to fulfil his promise, with the exception of one graphite drawing, Les Clés d’Antibes. (The drawing can still be seen in the hall of the Grimaldi.)

Instead, he donated the work he’d done there to the museum, stipulating that they should remain there permanently. “Anyone who wants to see them will have to come to Antibes,” he declared.

Picasso worked mainly at night, leaving Gilot in the afternoon in the house in Golfe-Juan. His friend Sima was invited to take photographs of him at work, and these pictures are included in the exhibition, intimate portraits of the artist in a playful and mischievous mood.

Picasso’s painting La Joie de Vivre (1946) is emblematic of his stay in Antibes, reflecting not only the Greco-Roman heritage of the old Mediterranean port, but also Picasso’s mood at the time. The composition is based on Greek mythology; it depicts a tambourine-playing nymph, wild horse-like creatures, and fauns dancing and playing the duale – a double-barrel flute typical of this part of France. It refers to the story of Antipolis (the Greek name for Antibes) and is also a homage to Gilot, his muse of the time.

La Joie de Vivre hangs on the second floor of the museum, in the space that became Picasso’s studio. Sunlight streams through its fortified windows and the Mediterranean glistens beyond. It’s not hard to see where his inspiration came from.

The painting is also intriguing because of the materials Picasso used. When he arrived in town there was a shortage of art materials, so he worked with what was available locally. Instead of canvas, the panel was made of asbestos-cement; Picasso also used boat paint procured from the quayside, which he applied using household paintbrushes. He reasoned that these materials would be perfect for the environment and the climate.

Another iconic painting here is the triptych Ulysse et les Sirènes (1947), in which the features of the Greek hero are represented by the insides of sea urchins; behind him we can see his boat and beyond that the snow-covered peaks of the Alps. Such is the influence of Antipolis in this painting that it is almost inconceivable that it could hang anywhere else.

However, not everything in this exhibition is sunlit. The show includes Picasso’s ‘vanités’, paintings made during the occupation of Paris. In these, his palette is reduced to shades of grey, ochre and black, symbolising the austerity and harshness of the war years. In one of his still lifes from this era, a mask and a pair of leeks form a skull and crossbones. There is also a jug. The metaphor for death is evident in the mask and leeks, but the pitcher of what can be assumed to be water represents a cleansing process, as if Picasso is ready to wash away the memories of war.

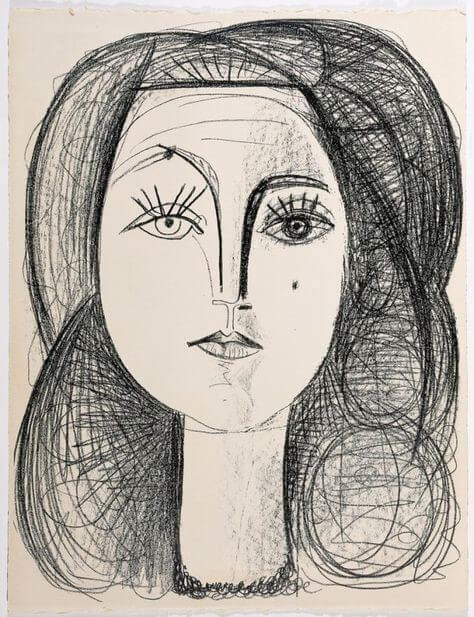

Nowhere is this new lease of life portrayed more clearly than in the image of Picasso’s lover, muse and soon-to-be-mother of his child. Françoise Gilot can be detected in nearly every painting, as a nymph, cat, moon goddess, flower and fish. A fantastic series of 13 graphite drawings are rhythmical portraits of her, each created in seconds without the artist’s pencil leaving the paper.

When Matisse came to visit the museum and saw the long plywood panel of the Reclining Woman, a painting of the nude body of Gilot splayed at perpendicular angles, he spent the afternoon sitting in front of it, sketching and taking notes, trying to figure out what Picasso had done with the top and bottom of the body.

The Age of Renewal in Antibes is more than an adjunct to this year’s round of Picasso shows. It’s an opportunity to breathe in the air and soak up the atmosphere of a place that inspired a man widely regarded as one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.

A.F.

Read also: Pablo Picasso: The Change – His Muse and Mistress