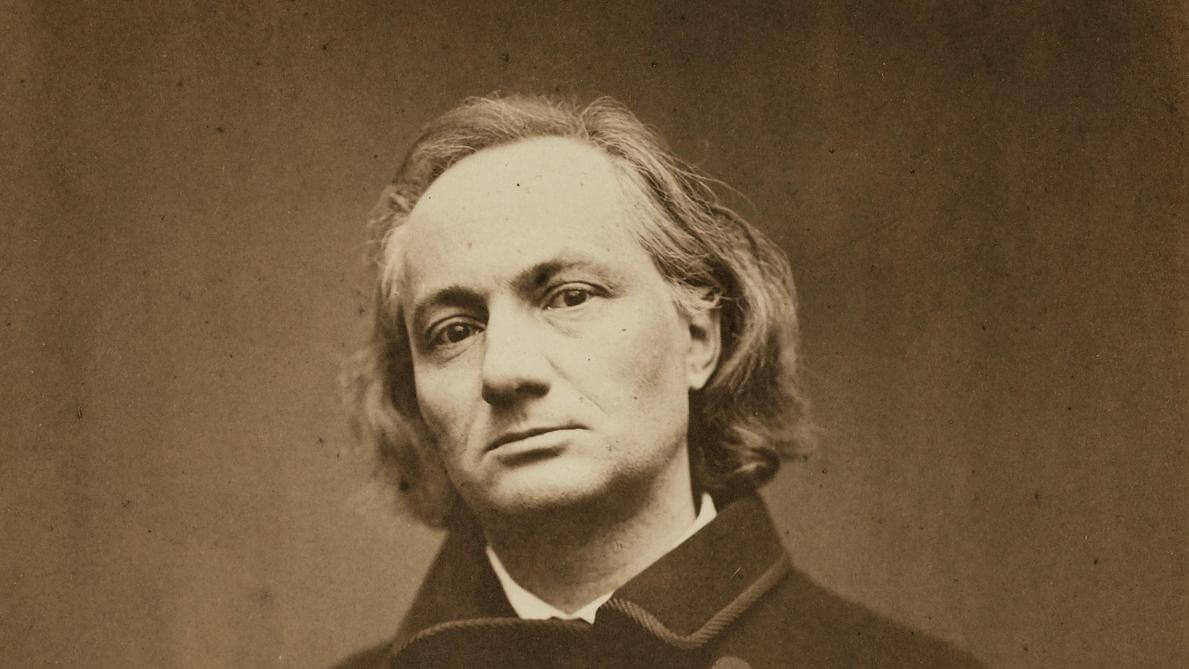

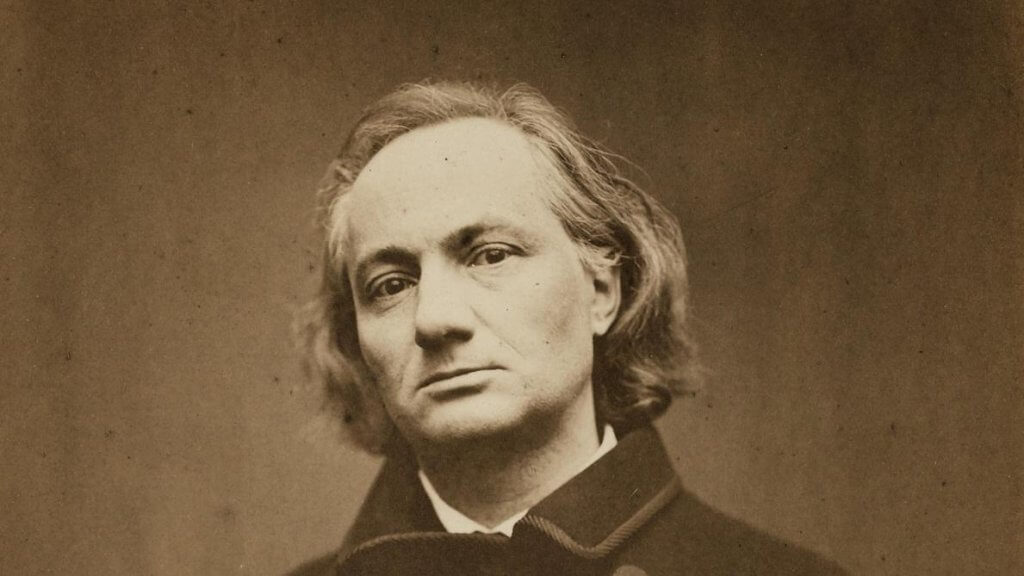

Charles Baudelaire inspirator and early influencer

An example of and for Life ??

by Arnold Heumakers/nrc

Amsterdam, July 29th 2021– One of the most remarkable prose poems in Baudelaire’s Le Spleen de Paris (1869) is about a mother whose son committed suicide. He hanged himself in the house of the painter, where the boy lived. The mother asks the painter (who tells the story) to give her the rope: “Her desperation, it seemed to me, must have made her so distraught, that she now cherished a tender love for what had served as her son’s instrument of death.” An expression of motherly love, described by the painter as ‘a completely self-evident, everyday phenomenon … which, unchanging in nature, cannot possibly mislead us’.

The portee, however, turns out to be exactly the opposite: motherly love can indeed mislead us. The mother has asked for the rope, the painter discovers, not out of loving devotion to her son, but because she wants to sell it cut into pieces to the neighbors, who show a macabre interest in it. Behold the ‘little trade’ with which ‘she intended to console herself’, Baudelaire concludes this prose poem, dedicated to his friend Édouard Manet.

The little black-romantic fable says something about the power of illusions and their ambiguity, and something about the human world in which mutual relationships seem to be impossible without illusions. ‘When the illusion disappears’, writes Baudelaire, ‘we perceive a strangely complex feeling, half of which consists of the lack of the vanished delusion, and of the other half of the pleasant surprise of the new, of the fact that it really is’. The disappearance of the illusion therefore does not lead to a moralistic lament about the unreliability of man and the world, but to a confirmation of the complexity of things.

Immense Cities

If the prose poems in Le spleen de Paris (now re-published in the translation by Jacob Groot) convey anything, it is this often surprising complexity, which Baudelaire expressly associates with ‘our stay in the immense cities’ and the ‘mixing of their innumerable cross-connections’. After all, the explosion of ever-changing impressions in the modern metropolis casts doubt on one’s own perception: everything is confusing, everything is new.

He considered no literary form better suited to express than ‘a poetic prose, musical without rhythm and rhyme, lithe and jerky enough to accommodate the lyrical movements of the soul, the swings of the dreaming and the convulsions. of conscience’.

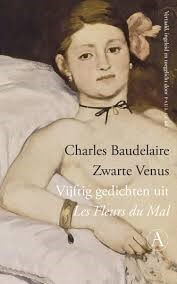

Baudelaire was not the inventor of the genre, that was Aloysius Bertrand, but where Bertrand (in his Gaspard de la Nuit from 1842) used the prose poem to evoke ‘the wonderful picturesque life of the past’, Baudelaire lets it loose on ‘the modern life’. In this, Le spleen de Paris resembles Les fleurs du mal (1857). Yet the ‘purpose’ is different, according to Jacob Groot, who has completely revised his 1980 translation, with brilliant results. The prose poems focus on the “splintered gaze” of a modern “flaneur”, overwhelmed by the rich chaos of the modern metropolis. Les fleurs du mal, in which the poems ‘sparkle monumentally’ (as Groot puts it beautifully), also deals with even more. Baudelaire himself regarded Le spleen de Paris as a ‘counterpart’ or ‘pendant’ of Les fleurs du mal, as witnessed by a letter to Victor Hugo, in which we also read: ‘I have tried to put into it all the bitterness and chagrin that I am full of. am’. The latter was less true of the poetry collection, if only because it had arisen earlier: pessimism and misanthropy increased in Baudelaire as he grew older. With as high or low point the furious ranting at the Belgians, whom he describes in a letter to Manet from 1864, three years before his death, as ‘dumbs, liars and thieves’ – with the exception of Félicien Rops, ‘the only true artist’ in Belgium.

Until now, Baudelaire’s correspondence was not available in Dutch. But on the occasion of this Baudelaire year (the poet was born 200 years ago), a representative selection, excellently translated by Kiki Coumans, has appeared in Privé domain. A number of letters to and about Baudelaire are also included, so that we get a nice epistolary portrait of this exemplary poète maudit.

Many of the letters are addressed to his mother, with whom Baudelaire had a complicated relationship to say the least. The prose poem discussed above, in which maternal love turns out to be an “illusion,” did not come out of the blue, although the emphasis on maternal calculation must probably be attributed to the bitter temper that had been given free rein in Le spleen de Paris. What exactly was going on between mother and son?

General

Baudelaire’s father died when his son was only five, after which his wife remarried General Jacques Aupick. Baudelaire was de facto raised by his mother and his stepfather. Both had high expectations of the boy – which he systematically fell short of. He was too playful, too dreamy, too lazy or too characterful, but never just good and successful. Refusing to betray a comrade, he was expelled from school. And when he expressed the wish to become a poet, the measure was full. Aupick sent him on a boat trip to India, which Baudelaire broke off halfway through, after which he went to study law in France.

In practice, he mainly wrote poems and threw away the capital inherited from his father. At least that’s how mother and stepfather thought about it, with the result that Baudelaire was placed under guardianship in September 1844. From that moment on, he could no longer freely dispose of his assets. Through the notary, he received a monthly allowance to live on, while his mother could give permission for extra money in case of emergency.

An unhealthy symbiosis of true love and mutual opportunism thus developed between mother and son: Mother still hoped to make a real ‘man’ of her beloved son, Baudelaire had no intention of giving up his poetic vocation, nor his bold life, without to separate from her emotionally and financially.

The correspondence bears witness to it. Baudelaire writes countless pleas to his mother, full of plans and promises of a ‘complete rejuvenation’, and at the end invariably the request for more money, at least to pay off the outstanding debts. Meanwhile, he made no secret of the fact that he considered the guardianship a “terrible humiliation” and that he “wasn’t like other people.” According to him, his mother did not understand him, even though we occasionally see her show appreciation for the ‘great beauty’ in Les fleurs du mal, despite the scandal (the collection led to a lawsuit, which Baudelaire lost) and all ‘unfortunately horrible and shocking descriptions’.

Civil decency

During his lifetime no reconciliation was possible between the bourgeois decency of the mother and the rebellious, romantic poetry of the son. It would come much later, after Baudelaire’s poetic rebellion was followed by many and he was recognized as one of the greatest poets of modern times. Leaving aside all the formal and thematic influence on Rimbaud, Mallarmé and many others (in the Netherlands for example on Menno Wigman, whose beautiful Baudelaire translations have recently been reissued), herein lies the exemplary dimension of this ‘doomed’ poetics: misunderstood in life, adored after death. This makes Baudelaire the literary equivalent of Vincent van Gogh, who plays an equally exemplary role in the visual arts.

That is not to say that everything between society and art is now a piece of cake. If that were the case, what could a Baudelaire-style rebellion mean? The bond between the two is no longer as intimately suffocating as that between Baudelaire and his mother, but there are certainly similarities. And they almost always have to do with money. Art and literature depend to a large extent on government subsidies, but their pride and justification derive mainly from the degree to which they deviate from the governing consensus, which can no longer be called unreservedly ‘bourgeois’ these days. The concrete details have changed, the double bind relationship has remained, and the reconciliation (in the form of canonization and financial gain) sometimes only comes posthumously now – if it comes at all, for few will be lucky 200 years after their birth. birth has yet to be translated and read.

Arnold Heumakers/NRC