Storytelling in and from Timbuktu

Part I

by: Anthony Ham

Amsterdam, September 12th 2021– As the sun neared the horizon, before the day’s final call to prayer, Azima Ag Mohamed Ali began his nightly walk through the sandy streets of Timbuktu in Mali. Along the way, first one, then a second friend fell into step alongside him. The greetings continued long after the friends met, with soft handshakes slipping together and apart, as each asked, over and again, after the health of their friends and families. This call-and-response carried deep into the conversation, as unhurried as their pace.

Swathed in voluminous robes of indigo, they passed through the streets of Timbuktu and continued out into the sand dunes, just beyond the city’s western outskirts. Finally free of the city, they sat down in the sand and brewed a pot of tea as the heat drained from the day.

The first tea is always strong like death,” Ag Mohamed Ali said. “The second is mild like life. And the third”, he smiled, “is sweet like love. You must drink all three.”

Like many Tuareg, the once-nomadic people of the Sahara Desert, Ag Mohamed Ali was born out in the desert, far beyond Timbuktu. His birth certificate states that he was born in 1970, but it is an estimate used only for official documents. No-one really knows for sure. “I think I am much older than that,” he said.

As a child in the Sahara, danger was never more than one big sandstorm away: “One day, when I was a small boy, I went to find water on my camel. On my way back to the camp, there was a sandstorm,” he said. “The sky was black and I couldn’t even see my hand. There was no warning, maybe five minutes at the most. I sat down and waited for the storm to end. It lasted maybe three hours. Then I went back to the camp. But then we had to go and find my father because he had gone to look for me.”

Ag Mohamed Ali was a teenager when he first saw the city that would later become his home. “I couldn’t believe the lights!” he remembered. Members of his family still live a semi-nomadic existence out in the desert. But when he became an adult, drought and the need to earn a living drove Ag Mohamed Ali into Timbuktu, where he set up a business as a guide for tourists who wanted to explore the Sahara.

His heart remained in the desert even when he had to be in the city. He refused to get a fixed-line telephone lest he come to depend upon it and never be able to leave. When he had no clients, he would escape to the desert, spending months at a time camping out, drinking tea with friends and sleeping under the stars. Whenever he had to be in town, the nightly foray into the dunes just outside the city was his escape.

As Ag Mohamed Ali travelled between desert and town, he bridged geographic spaces and spanned the ages, moving between a time of ancient desert traditions and the demands of modern life. Before tourists stopped coming to the Sahara , he was a tour guide; but among his own people, he remains a keeper of traditions and a teller of stories. And passing on those stories has become an obsession.

“My children were born in the desert, as is our custom,” he said. “We live in Timbuktu and I want them to go to school, not like me.” Ag Mohamed Ali can speak seven languages though he never learned to read or write. “But one day I will also take them to the desert for a long time, so that they can learn about the desert and know it well, so they don’t lose the connection.”

By the 16th Century, more people – 100,000 – lived in Timbuktu than lived in London

It has been nearly a decade since Ag Mohamed Ali has been able to show the beauty of the region to travellers. Rebellions and conflict across the Sahel and Sahara have stopped the flow of tourists, causing great hardship to the peoples of the desert, especially guides like Ag Mohamed Ali. His stories now ring like echoes of the halcyon days of Saharan travel.

Even confronted with such difficulties, Ag Mohamed Ali looks forward to the day when travellers can return.

For Ag Mohamed Ali and his children, the Sahara and Timbuktu is home. For the outside world, these places have come to represent the outer reaches of the known world.

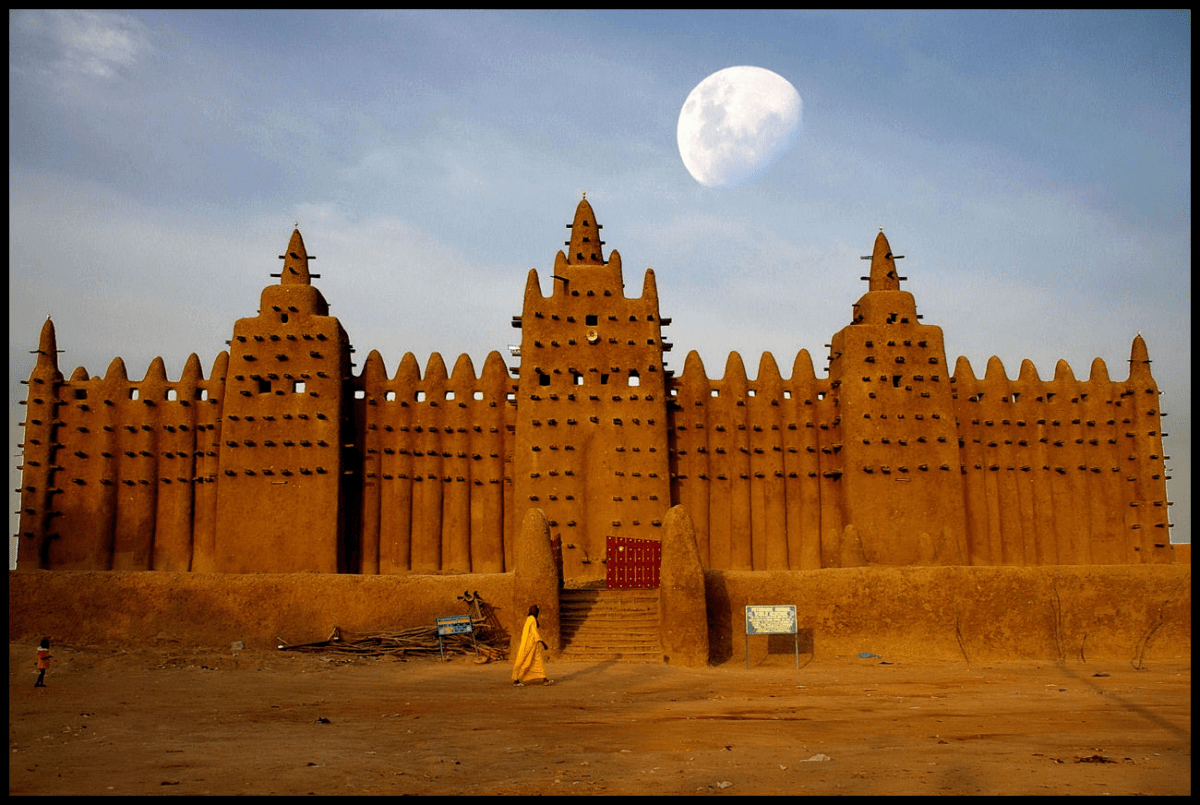

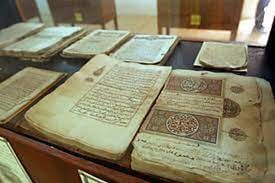

In the Middle Ages, Timbuktu stood at the confluence of some of Africa’s most lucrative trade routes. It was where the great salt caravans of the Sahara met the trade that coursed along the Niger River. Salt, gold, ivory and luxury European goods like linen, perfumes and glass all passed through a city that was, at the time, one of the richest on Earth. By the 16th Century, more people – 100,000 – lived in Timbuktu than lived in London. The city had nearly 200 schools and a university that drew scholars from as far away as Granada and Baghdad. It was known for its libraries of priceless manuscripts.

Ag Mohamed Ali initiated travellers into Timbuktu’s secrets. He took them to the private family libraries that still held manuscripts from Timbuktu’s golden age – biographies of the Prophet Muhammad on pages of gold leaf and scientific treatises from the great Islamic scholars of the day. He showed them the Dyingerey Ber Mosque, where no-one has dared to open an ancient palm-wood door since the 12th Century; when the door opens, a local legend warns, evil will escape into the world.

As he shared the stories of Timbuktu with visitors, Ag Mohamed Ali came to understand the outside world’s obsession with the city. He watched as tourists tried to reconcile Timbuktu’s storied past with the modern sand-blown streets and ramshackle mud dwellings. He took them to the markets where camels still arrived bearing slabs of salt from the deep-Saharan mines of Taoudenni. And he hurried them to shelter as the harmattan, a red desert wind, turned the sky dark in a blizzard of sand.

As a guide, Ag Mohamed Ali made friends from around the world, and he visited some in Europe. It was, to him, an alien world, just as Timbuktu remains for many around the globe. “The first time I was in Europe,” he said, “and I saw water just lying on the ground, I thought ‘these people are crazy’.” And everything moved at a speed that was unthinkable in the Sahara. “In the desert we have infinite time but no water,” he said. “In Europe, you have plenty of water but no time.”

And yet, even so far from the desert, Ag Mohamed Ali found a connection: “The first time I saw the ocean in Barcelona, I cried because it is like the desert. You cannot see its end.”

Ag Mohamed Ali’s travels also helped him understand the appeal of Timbuktu, because Paris and Barcelona were as unbelievable to him as Timbuktu is to much of the rest of the world. He went to a football match at Barcelona’s Camp Nou stadium. “In the one place there were more people than in all Timbuktu,” he remembered. He would later found a Timbuktu chapter of the FC Barcelona fan club.

When travellers wanted to see more of the Sahara, Ag Mohamed Ali took them to deep-desert Araouane, a sand-drowned town 270km north of Timbuktu. To get to Araouane, travellers must cross the Taganet sand sheet, which stretches, uninterrupted, to the far horizon. For the last 100km, there isn’t a single tree.

Araouane itself has the appearance of a shipwreck. A number of its buildings have disappeared beneath the sands. Many of the houses that remain, even a mosque, lie half-submerged by the dunes that envelope the town. For weeks on end, the wind blows without respite, and sounds like ocean waves breaking on the shore. Women carry water from the well, leaning into the wind. Without the wells, life would be impossible here; sometimes it doesn’t rain in Araouane for decades. Sand is everywhere, and nothing of any value, save for a single, forlorn wild date tree, can grow here.

Before, to show that you were strong, you were a nomad,” Ag Mohamed Ali said, when asked why people would live in such a place. “Now, to show you are strong, you stay in one place, you become sedentary. That is why the people of Araouane stay here. It is to show that Araouane exists.”

And yet, for the tourists who visited there was undoubtedly more to it than that. There was something here that produced a sensation akin to exhilaration. It was the awe of vast skies and big horizons. It was the intimacy of lantern light flickering on mud ceilings as Ag Mohamed Ali told stories of salt caravans lost in sandstorms, stories that told of the uncanny ability of desert guides to find their way home in a world devoid of landmarks; sometimes they did this by tasting the sand or assessing its colour. It was the sand ridges perfectly sculpted by ceaseless winds, or the runic patterns written by wind on sand. And in the delicious remoteness lay an austere, end-of-the-world beauty.

Even as conflicts across North and West Africa have prevented visitors from coming to Timbuktu and Araouane for now, Ag Mohamed Ali wouldn’t change where he lives for anything. “When I am in the desert, I feel like a free man. I feel safe and I am never afraid. Here I can think. Here I can see everything. It is who I am. I never want to leave. It is my home.”

End Part I

Read also Part 2

Anthony Ham is a Madrid based journalist and writer