Incomprehensible Rainer Maria Rilke

And yet so rich and easy

Part II

Amsterdam, 30 june 2021– One often hears that Rilke’s poetry is so difficult, so very incomprehensible. This is true for his mystical late work, but not for the poems from his middle period. These are surprisingly concrete and clear, if you make any effort to follow the delicate German.

Now that a bilingual edition has been published not only of the Neue Gedichte, but also of its sequel, Der Neuen Gedichte anderer Teil, German can no longer be an insurmountable barrier. Nor does Dutch, for that matter, because Peter Verstegen is a down-to-earth Dutchman who tolerates no vagueness in his translations.

New poems.

The other part is even so accessible that the haze hanging around Rilke is radically torn away. His image as a God-sent poet turns out to be completely wrong, thanks to the translations. On the contrary, the author emerges as a plodding human being who goes out of his way to find interesting topics. Rilke traveled drowsy: from Paris to Capri and Naples and Venice and St Petersburg and then back to Paris – where he also ran out of steam in his hunt for useful lyrical material.

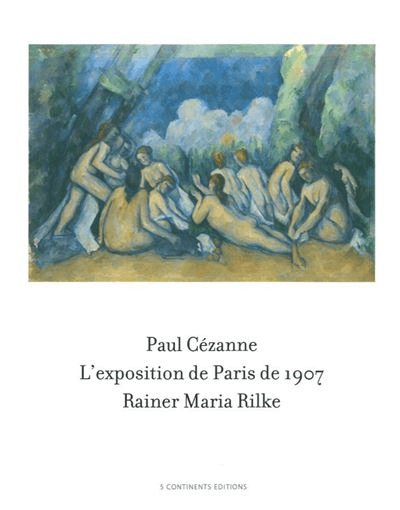

Visits to Notre-Dame and the Louvre were supposed to provide him with inspiration: Rilke’s art largely stems from the art of others. Twice a painting by Cezanne serves as an example (see ‘The elopement’ and ‘The temptation’) and twice a Manet (‘The balcony’, ‘The Reader’). The mythical beasts in the ridge of Notre-Dame figure in several of his poems, and the closing poem is a poetic imitation of a Buddha statue noted in Rodin’s garden: Buddha in der Glorie.

Rilke, actually a boy from Prague, temporarily settles in Paris especially for the sculptor Auguste Rodin; he is even his private secretary for eight months. Rilke takes on Rodin’s muscular work ethic (Travailler, toujours travailler!) and also learns from him how to value what you see while still moving into it. Ding-Poem Rilke calls his attempts to banish the lyrical I, the I with its annoying whims and whims. They squeeze themselves, Rilke thinks, Rodin thinks, all too often between artist and work of art; those screaming for attention obstruct the view of the essence of the observed.

Rilke thus tries to observe as objectively as possible and to banish his emotions. Because he also shows more interest in art than in things taken from life, his New Poems have something very distant. They are elegant and well-groomed; there is no flaw in it. Invulnerable, they are almost perfect, with a shape as solid as a prison. Like the caged beast in Der Panther, the people sung by Rilke have so little space. Their cage is precious, though. Jasper and jade, jasmine and Najaden: Rainer Maria is not satisfied with less sound materials.

Gemstones, medallions and marble platforms are not only found by this beauty-loving poet in existing paintings, but also in the fairytale-like scenes that he himself adds. Old noble families exert an irresistible attraction on him; he likes to stroll through their parks, in fantasy and in reality – for Rilke had the talent of endearing himself to maidens and baronesses. If they invited him to their castle, the poet would have killed two birds with one stone because that way he could travel to another country as well as to another time.

He lustily fables about Middle Ages, Renaissance and prehistory, about kings and knights, dragon slayers and chess damsels, about coats of arms and white greyhounds. The poem ‘The Arrival’ (Die Anfahrt), for example, reads as follows in translation: ‘Was that impetus in the carriage that bowed? Or in the look with which one saw the baroque angel figures between blue bells and full of memory in the field and held it and then let it go, before the castle park urgently closed around this drive it touched and offered its leafy roof, then suddenly let go: for there was the gate which now, imperiously demanding it seemed, forced the long front view to swing, after which it stopped. A slipping gleam flew past the glass door; a greyhound pressed from her opening, carrying its chapped flanks the flat steps of the landing.’

As usual in a sonnet, here too after the eighth line there is a turn: a cinematic turn this time. Because the camera that could be on the moving carriage no longer zooms in on the park but on the gate that is approaching at lightning speed. The poem is action packed but without feverishness. Yes, this movement study also exudes tranquility

And, yes again, this movement étude also exudes calm and quiet grandeur. Where is the fear, the turmoil, the impressive panic of Rilke’s alter ego Malte

Coming up Part III

Second part of Rilke translated; The haze around the poet snatched

Rainer Maria Rilke: New Poems. The other part. Translated and commented by Peter Verstegen. G.A. van Oorschot, 350 p. 39,- (pbk)/59,- (born)