Al-Andalus, Civilisation and Slavery

Measuring Today with Yesterdays Tools

Amsterdam, 19 feb. 2021–

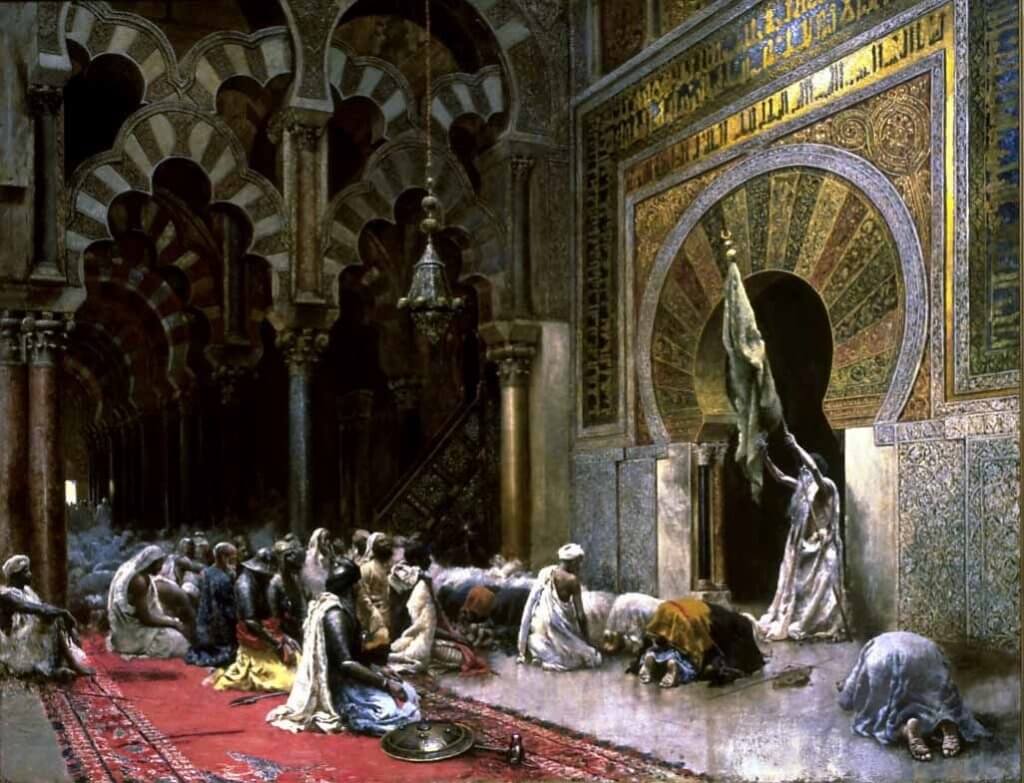

The Alhambra in Granada, central Spain, is one of the many pinnacles of Islamic architecture.

Toured by the art historian José Miguel Puerta Vílchez, it is a revelation and satisfies a lot of curiosity about the influence of Islam in Europe.

He has written extensively about the thousands of inscriptions decorating the walls. According to him, the Alhambra is a building and a book in one.

Vílchez mentioned in passing that the Alhambra was built with the help of Christian slaves. The palace of Charles V – which was built by the Catholic monarchs in the center of the complex after the Reconquista – was in turn built by Muslim slaves. In other words, this peak of civilization is also built on a foundation of oppression.

In all the heated discussions about the abolition of the term “Golden Age”, little reference is made to the use of similar terms in a different historical context. Yet it is common to refer to Al-Andalus – the part of Spain that was ruled by Muslims until 1492 – as part of a “golden age” of Islam.

Christian civilization clearly lagged behind. Already in his classic The Land of Rembrand (1882), Conrad Busken Huet judges harshly about the culture of the Crusaders: ‘Having no architectural forms other than the bulky or shabby abbeys of Bloemhof and Rozeveld, the Moorish architecture fills them with an admiration that they would like to put into words.’

But according to him they are not able to do that: “But they are still too much bushmen of the North to be able to respect what they do not understand. Their Christianity and their racial hatred make them see in the works of art of the Mohammedans the works of the Evil One.. So this “racial hatred” was already clear to Busken Huet at the end of the nineteenth century.

In any case, I notice that in the past people often spoke critically about the past than we are now inclined to think. Take E. Molt’s Fatherland and Dutch History (1927). Of course, there is a lot to haggle about that popular book, but to think that the colonial era is just a song of praise, no, that’s not right.

Thus we read about the East India Company: “The suffering inflicted on the Natives by the greed of the Westerner was greatly increased by the ill stature of those who visited the East as fortune seekers.

These troops acted “against the wandering and wicked race, for which they saw the natives, with all the tyranny of men, seized by greed as by a running fever.”

Historian Molt’s “Golden Age” was not an unambiguous story. There are more examples of earlier historiography that show that not everything was gold that shone in the seventeenth century. There is imaging, but also something like imaging about that image. The statement that the past was only recently glorified is rather superficial.

Thus Molt concluded: “It may well be said that blood and tears clung to the capitals that made Amsterdam a pearl among Europe’s capitals, which gave the Dutch wholesaler a power and prestige greater than what many a monarch had to dispose of.”

That blood and those tears were visible a century ago.

Wandering through the mesmerizing and exquisite beautiful halls of the Alhambra, I wondered if those so keen to banish the term “Golden Age” would no longer want to speak of Al-Andalus as a golden age of Islam. How often has this period been referred to as an example of the coexistence of Muslims, Christians and Jews – even though we know, for example, of the pogrom against Jews in 1066?

It is undeniable: measured at this time, both the tolerance in Granada and Amsterdam was limited. In our Golden Age, Jews could not marry Christians and Catholics were second-class citizens who had to practice their faith in secret churches. Yet the Republic was regarded as an island of tolerance in a sea of absolutism.

It is good that we discuss slavery records and. And it is good that the colonial era is receiving more attention in education. But to retroactively measure these centuries against today’s standards quickly ends in denial of the progress of which both Granada and Amsterdam are symbols. It must be possible to bring together appreciation and criticism – even when we are talking about the golden age of a civilization.

Paul Scheffer