The Complexity of the Human Brain

Unraveled

Amsterdam, 8 June 2021–Our brain is the most complex object in the known universe – so we’ll need to map it in formidable detail to track down memory, thought and identity.

A strange contraption, a cross between a deli meat slicer and a reel-to-reel film projector, sits in a windowless room in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

It whirs along unsupervised for days at a time, only visited occasionally by Narayanan Kasthuri, a mop-haired postdoc at Harvard University, who examines the strip of film spewing out.

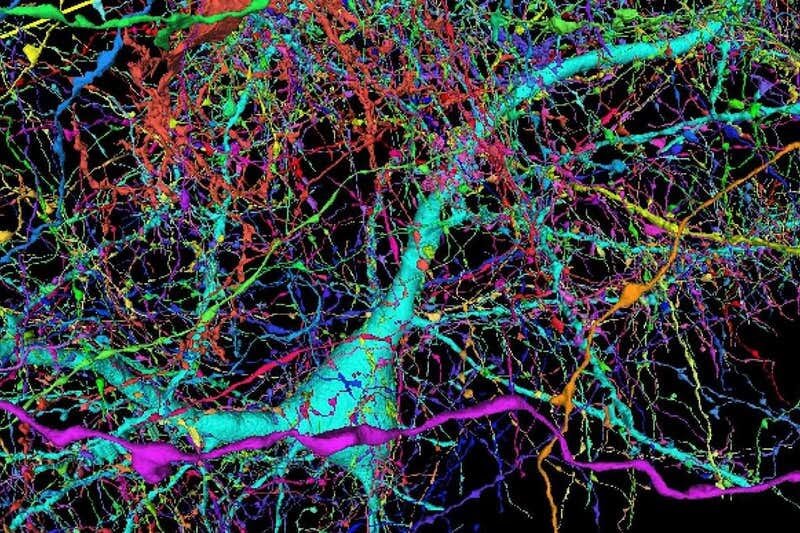

It may seem unlikely, but what’s going on here may revolutionise neuroscience. Spaced every centimetre along the film are tiny dots, each of which is a slice of mouse brain, one-thousandth the thickness of a sheet of aluminium foil. This particular roll of film contains 6000 slices, representing a speck of brain the size of a grain of salt.

The slices of brain will be turned into digital images by an automated electron microscope. A computer will read those images, trace the outlines of nerve cells, and stack the pictures into a 3D reconstruction.

In the jargon, they are building the mouse “connectome”, named in line with the term “genome” for the sequence of all of an organism’s genes, “proteome” for all its proteins, and so on.

It’s an epic undertaking. The full mouse connectome would produce hundreds of times more data than can be found on all of Google’s computers, says Jeffrey Lichtman, the neuroanatomist leading the Harvard team. And yet it’s just the beginning.

Rotifers 24.000 years asleep

Researchers have successfully revived one of these small animals after 24,000 years in permafrost

A tiny animal called a rotifer has been revived after spending 24,000 years frozen in permafrost.

It is the longest a rotifer has been observed to survive in such extreme cold.

While simple organisms like bacteria can often survive millennia in permafrost, “this is an animal with a nervous system and brain and everything”, says Stas Malavin at the Pushchino Scientific Center for Biological Research RAS in Russia.

It isn’t quite a record – nematode worms have purportedly been revived from permafrost after 30,000 years – but no rotifer has been known to endure for so long.

Malavin and his team drilled into permafrost near the Alazeya river in north-east Siberia, Russia, in 2015.

They found a single rotifer, a worm-like creature less than a quarter of a millimetre long. When the researchers warmed it up and gave it food, it became active. It also reproduced, because it is a bdelloid rotifer that can clone itself without the need for a sexual partner.

Microbes survive 30,000 years inside a salt crystal

“We are quite confident that this is a new species for science,” says Malavin. He and his team sequenced the rotifer’s genome and found it was most similar to a species called Adineta vaga, which is thought to include multiple subspecies that haven’t been properly identified.

The researchers used accelerator mass spectrometry to date organic remains that were found with the rotifer. They were between 23,960 and 24,485 years old, suggesting the rotifer was frozen into the permafrost at the same time.

Modern rotifers seem to have a similar ability to survive being frozen. Malavin’s team froze individuals from different modern species, as well as some of the offspring of the ancient rotifer, at -15°C for a week. Both groups were equally freeze-tolerant, with similar survival rates.

It isn’t clear how they do it, according to Malavin. In recent years, it has become clear that freeze-tolerant organisms have a multitude of survival mechanisms, not just one, and they don’t all use the same ones. “The mechanisms are surprisingly poorly known, I would say,” says Malavin.

What’s more, it is also unclear how long rotifers or other freeze-tolerant animals could endure in permafrost.

Malavin says it will depend on whether their metabolism stops completely or just becomes extremely slow. If it stops, they could theoretically survive much longer than 24,000 years – with the limit probably being set by background radiation that slowly damaged their DNA.

But if their metabolism only slows, eventually they would need a source of energy – food – to keep going.

AF: source Journal reference: Current Biology