Being here is more than wonderful

Including pain And sorrow

Part VIII

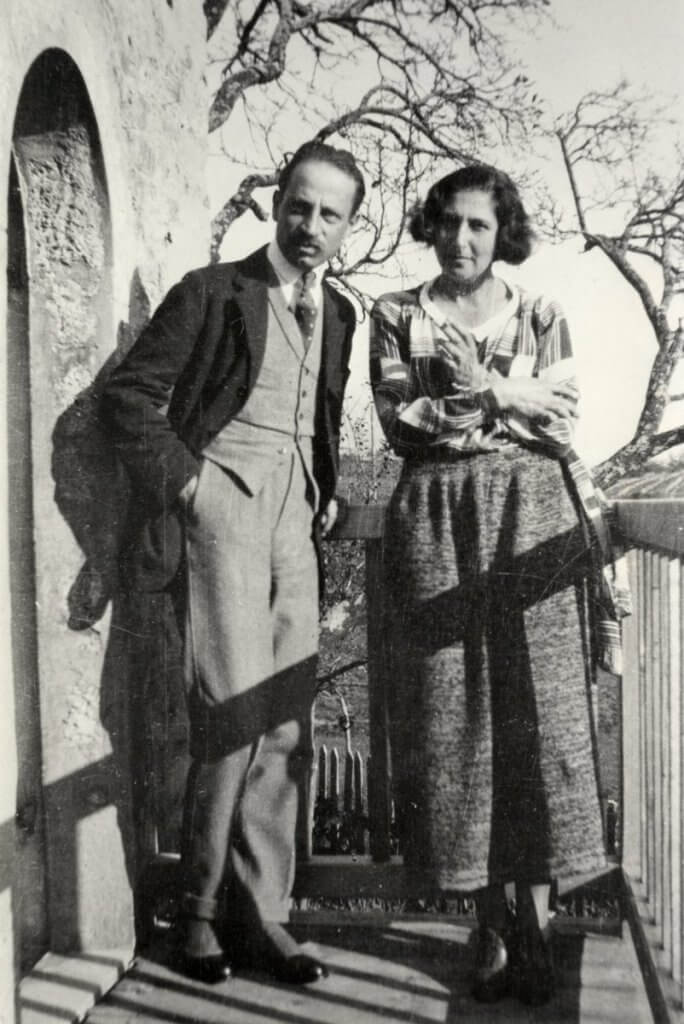

Amsterdam, June 30 2021– According to Robert Musil, Rainer Maria Rilke was the greatest German-speaking poet since the Middle Ages.

He had made the poem “perfect for the first time.” Musil made his oft-quoted statements in a 1926 article shortly after Rilke’s death, and at first glance his preference seems rather surprising. Musil is, after all, known as the great essayist novelist, Rilke precisely as an emotional person and lyricist pur sang.

But on closer inspection, the similarities turn out to be almost as great as the differences. Both were great innovators in their fields and promoted utopian thinking. Both realized that they were living in a time of transition and that there were fewer and fewer certainties for the modern intellectual. “Everything is subject to an invisible but never resting process of change,” it reads in chapter 62 of Musils Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften. But this core idea of Musil’s novel is also central to Rilke’s famous cycle Duineser Elegien, which he started in 1912 at Duino Castle near Trieste and which he was only able to finish in 1922 in Muzot, Switzerland.

Rilke regarded his recently published Duineser Elegien in a new translation as his most important work. He had resolved to put into words the problems of modern man, to formulate a meaning of existence; and it is the combination of rather pompous philosophical ideas and characteristic imagery that lends this work its own charm as well as degree of difficulty.

Due to its hermetic character, the late work of the poet has always been less popular than the collections Neue Gedichte (1908) or Buch der Bilder (1904). On the other hand, late lyricism has always captured the imagination of philosophers and illustrious thinkers; Rilke’s exegetes include Heidegger, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Romano Guardini, and Erich Heller.

Atze van Wieren is responsible for the new translation under the title De elegies van Duino, and it has turned out to be a successful piece of work. Van Wieren’s translation is slightly more modern and ‘more common’ than the sometimes rather solemnly archaic version from 1978 by the Nijmegen professor W. Bronzwaer, who died young, who still used words such as ‘cousins’ and ‘goose’ or formulations such as ‘prijs den angel’ and ‘stupid’. Van Wieren is more concise and sometimes seems to take a little more risk than his predecessor.

School of Life

Whichever translation one ultimately prefers, of course, depends on taste. Bronzwaer’s solemn style still fits wonderfully with a timeless poet like Rilke, and in one respect his edition remains indispensable: his commentary is superior.

Epigram-esque

It is striking that Rilke uses the concept of ‘elegy’ (originally a poem in metrical distycha) almost arbitrarily. Sometimes it comes close to the modern free verse. Just as remarkable is the widely varying length of the verses. Almost endless, extremely pathetic streams of thoughts are interrupted by short epigram-like notes.

Rilke opens the first elegy with the famous exclamation “Who, if I cried, would hear me from the ranks of the angels,” which resembles an existential primordial cry. The poet laments the human insecurity and notes that we are ‘not so at home and familiar/in our explained world’. The first elegy also mentions the regularly returning angel, who in Rilke is not a biblical appearance but a symbolic figure who is at home in life as well as in death – the poet did not make a strict division between the two domains.

In the fourth elegy the theme of the human deficiency from the first elegy is taken up again. Man is a split being due to his capacity for reflection, our consciousness does not allow us to experience life as Dasein; this distinguishes us from the animals, and also from children, who are “free from death,” as it reads in the thematically related Eighth Elegy. Rilke was probably influenced here by Heinrich von Kleist, who expressed similar ideas in his essay ‘Über das Marionettentheater’ (1810). The influence of German Romanticism is already striking in these elegies, because Rilke has also prompted Hölderlin (patheticism) or Novalis (synthesis of life and death).

After the lamentations of the first half, the seventh elegy is followed by a cover, better yet a praise song to life that culminates in the phrase: ‘To be here is glorious’.

For Rilke, boasting of earthly existence – love, sexuality, nature, art and poetry – is not a simple optimism, but inextricably linked to the acceptance of pain, sadness and death. In a famous explanatory letter to the Polish translator Witold von Hulewicz, Rilke writes: “In the Elegies, acceptance of life and acceptance of death appear to be one and the same. […] there is neither a here nor a there, there is only the great unity. […]

Transience everywhere leads to a deep being. And therefore we must use all forms of what is here not only in their temporality, but, as far as we can, place them within those higher meanings in which we partake.

But not in a Christian sense (which I distance myself more and more passionately from): the point is, in a purely earthly, deep-earthly consciousness, to place everything we see and touch here in the wider, the widest context.

Genitals of the money

In the last elegies, Rilke criticizes modern times. He laments the ‘too much noise’ and ‘the spurious silence’, or he paints – as in the tenth elegy – the vain amusement of people, their hunger for status, property and money (somewhere there is mention of ‘the genitals of the money ‘), which alienates people from the essential things of life.

Rilke has liked and frequently been inspired by the visual arts throughout his work.

In his Paris years he worked as a private secretary for the sculptor Auguste Rodin, who was as important to his artistic development as the painter Paul Cézanne. From Cézanne and Rodin, Rilke got to know the total surrender to work (‘il faut travailler, rien que travailler’, the sculptor had told him), but also the sober craftsmanship, the impartial look at the most everyday things. At the beginning of the 20th century (he had moved to Paris in 1902), this led to a new conception of art for the previously rather neo-romantic Rilke, which culminated in the collection Neue Gedichte and in the diary novel Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge. .

Rilke has published two wonderful, complementary monographs on Cézanne and Rodin. The recently published Letters about Cézanne (a reissue of an almost twenty-year-old edition) consists of epistles that the poet sent from Paris to his wife who remained in Germany in 1907. Rilke expresses in glowing terms his admiration for the work of Cézanne, who died one year earlier, and interprets his still lifes and portraits with great sense of detail. The confrontation with the groundbreaking art in the Paris Salon d’Automne caused a shock of recognition in his mind: ‘It is the turning point in this painting, which I recognized because I myself had just come to the point in my work whether I somehow approached, since long probably prepared for this one thing on which so much depends’.

End of the series of eight essays on Rainer Maria Rilke

Correction / Rectified

Due to an editorial error, a line of Rilke’s poetry has been misrepresented in Rainer Maria Rilke’s The elegies of Duino (Boeken, 17.08.07). The correct quote is: “Who, if I cried, would hear me from among the rows of the angels.”

In the new translation of his ‘Laments’, Rainer Maria Rilke seems remarkably modern. The praise of earthly existence goes hand in hand with the acceptance of pain and sorrow.

Rainer Maria Rilke: The Elegies of Duino. Translated by Atze van Wieren. IJzer Publishers, 109 pages. €17.50

Rainer Maria Rilke: Letters about Cezanne. Translated by Philip van der Eijk. L.J. Peat, 111 pages. €15,–